What Does the Guru Granth Sahib Actually Say?

A computational analysis of 60K lines, 6 languages, 18 authors. Every word. Every Hymn. Every divine name.

(This post is 9,100 words long. It is best read on substack. Your email will truncate it. Repository source code. see docs/ for the entire analysis, my data science post on how the project was delivered)

I am a voracious reader and practitioner of Indian philosophies. But I always felt that as a not-so-fluent reader of Punjabi, I couldn’t truly understand the Guru Granth Sahib – the seminal text, nay the Living Guru, of the Sikhs. My understanding and interpretation were outsourced to Granthis (clerics). That, as a modern human, felt like being illiterate.

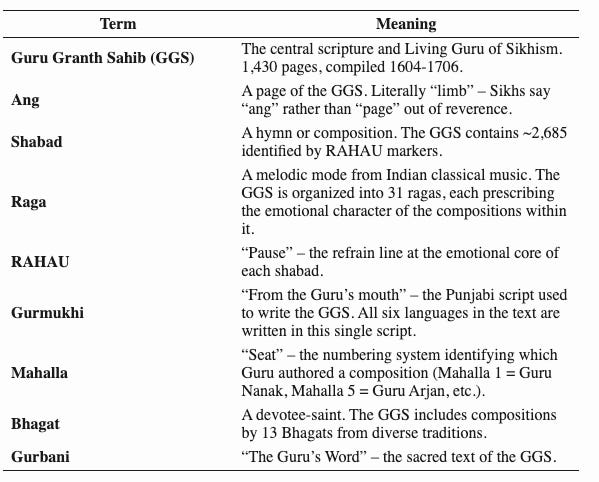

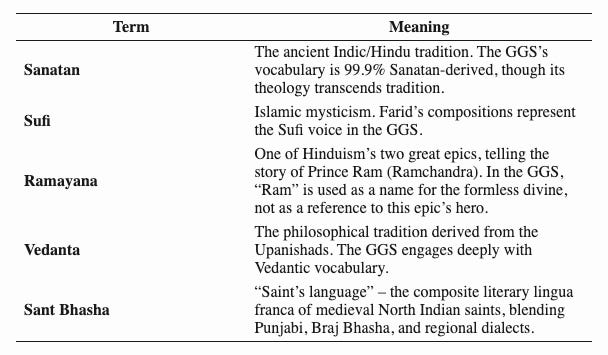

I was always curious to answer some basic questions. What’s the core philosophy? Because different parts of the text felt different – Advaita (non-dual)? Bhakti (devotional)? Stoicism? Why music? What’s the influence of Sanatan (Hinduism) or Islam? As far as I know, the GGS is the only scripture where the Gurus have written every word themselves, and the only spiritual text where saints from different religions are quoted alongside the Gurus’ own compositions – deliberately placed there to bring in lessons from those traditions.

Then I discovered one reason it had been so inaccessible, even though my listening Punjabi is excellent: there are six languages woven into the text, all written in Gurmukhi (the Punjabi script). Par for the course when a text is composed over 200 years by ten Gurus and thirteen saints from across the subcontinent.

So here’s what I decided to do over a long weekend. Armed with ChatGPT (for the product requirements document) and Claude Code (for the pipeline), I went to analyze the raw Gurmukhi text directly – no English translation driving the analysis, no intermediary interpretation. Every line. Every word. Every divine name. Every metaphor. Every critique. 124 theological entities tracked across 346 spelling variants. Ten iterations of checking and rechecking to keep my biases out.

Here’s what the data says.

The Mool Mantar (Core Mantra)

Every recitation of the Guru Granth Sahib begins with one line. Every Sikh knows it by heart. I didn’t realize until the data came back that the entire book is an elaboration of it.

ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ

Ik Oankaar Sat Naam Karta Purakh Nirbhau Nirvair Akaal Moorat Ajooni Saibhang Gur Prasaad

Word by word:

Ik Oankaar – One creator, one sound, one field, one spirit.

Sat Naam – Truth is the Name.

Karta Purakh – It does everything. The field and the creation are not separate.

Nirbhau – Without fear.

Nirvair – Without enmity.

Akaal Moorat – Timeless. Eternal. Beyond time.

Ajooni – Beyond species. In Sikh theology, “jooni” means species or life-form – the GGS references 8.4 million jooni that the soul cycles through. A-jooni means the divine is not any life-form, not any species. Beyond all 8.4 million categories of existence. Beyond the cycle of birth and death entirely.

Saibhang – Self-existent, self-illuminated. Existing by its own nature, without an external creator.

Gur Prasaad – Realized only through the grace of the Guru.

This is the pehli paudi – the first step. No idol, no incarnation, no mythology. Nine attributes of the formless, compressed into a single line. The remaining 1,430 pages are a commentary on it.

The DNA, Not Just the Preamble

The Mool Mantar isn’t just an opening prayer. It reappears 28 times across the text – from ang (page) 1 to ang 1,410 – punctuating the entire book like a heartbeat.

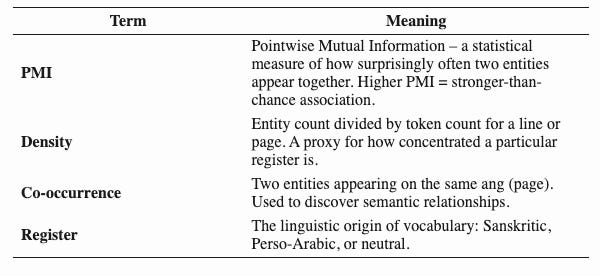

But here’s what the data revealed that I didn’t expect: even outside those 28 repetitions, the Mool Mantar’s attributes travel together through the compositions themselves. Co-occurrence analysis shows that AJOONI, AKAL, SATNAM, NIRVAIR, NIRBHAU, and MOORAT form the tightest theological cluster in the entire corpus. The statistical association between these terms ranges from PMI 2.7 to 5.0 (PMI, or Pointwise Mutual Information, measures how surprisingly often two words appear together – higher means a stronger-than-chance association). When a Guru invokes one of these attributes anywhere in the text, the others tend to appear alongside it. They move as a pack.

Here’s what that looks like in practice. At ang 916, deep in Raga Ramkali (a contemplative melodic mode), Guru Arjan writes:

ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੰਭਉ ਕਲਿ ਅੰਧਕਾਰ ਦੀਪਾਈ

Timeless Form, Beyond Birth, Self-Illuminated – a lamp in the darkness of this age.

Two lines later:

ਏਕੰਕਾਰੁ ਨਿਰੰਜਨੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਸਭ ਜਲਿ ਥਲਿ ਰਹਿਆ ਸਮਾਈ

The One Creator, Unblemished, Without Fear – pervading all waters and lands.

Four Mool Mantar attributes – AKAL, MOORAT, AJOONI, NIRBHAU – woven into the poetry of a composition 915 pages after the opening line. The Mool Mantar isn’t a preamble. It’s the theological DNA of the entire text, and you can find it echoing in compositions across centuries and authors.

Every word in that opening line describes the formless. This is Advaita in one breath.

What Makes the GGS Unique

Eighteen authors across two hundred years. The prophets wrote it themselves – no intermediary scribes interpreting decades later. That alone is a remarkable provenance claim. But the GGS goes further.

Structural Inclusion

The Gurus deliberately placed compositions by saints from outside the Sikh tradition alongside their own, in their holiest text, on equal footing:

Kabir (4,187 lines, 6.9% of the text) – a Muslim weaver from Varanasi.

Ravidas (475 lines) – a leather-worker, considered “untouchable” by caste Hindus.

Farid (158 lines) – a Sufi mystic.

Namdev (257 lines) – a Marathi tailor-saint.

Plus nine more Bhagats (devotee-saints) from diverse backgrounds.

In the 15th-17th century, this wasn’t tolerance. It was structural inclusion – placing these voices in your most sacred text, alongside the Gurus’ own words. Kabir alone contributes more lines than two of the six Gurus (Guru Angad and Guru Tegh Bahadur) individually.

A Text Written Across Generations

Some compositions in the GGS were deliberately left incomplete by earlier Gurus, with the expectation that a Guru generations later would come and complete the poem. And they did. This is not collaborative editing in the modern sense – these are authors separated by decades, sometimes over a century, completing each other’s verses as though continuing a single conversation. The Gurus saw themselves as one light (jot) passing through different bodies. The text is built on that continuity – a prophetic confidence that the voice would not break.

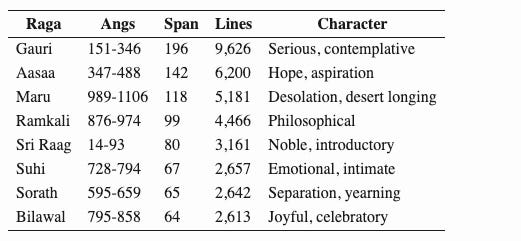

Poetry Set to Music

Every composition in the GGS is assigned one of 31 ragas – melodic modes from Indian classical music. Each raga has emotional and seasonal character: Gauri for contemplation, Aasaa for hope, Maru for desert longing, Bilawal for joy. The text doesn’t just tell you what to think. It prescribes how to feel while you sing it. Built-in emotional instructions – not just words but the feelings the Gurus intended you to experience.

The Living Guru

In 1708, Guru Gobind Singh declared the GGS as the eternal, living Guru. This isn’t symbolic – the ethos is ingrained in daily practice. Sikhs sit before it, consult it, bow to it, put it to bed at night, and wake it in the morning. It is treated as a living human being, not a book.

Guru Gobind Singh’s Restraint

Guru Gobind Singh was himself a prolific poet in Punjabi and Persian – his compositions fill the entire Dasam Granth (a separate collection of his writings). He compiled the final edition of the GGS (the Damdami Bir, 1706), adding Guru Tegh Bahadur’s 605 lines. Yet he deliberately excluded every word of his own. For a saint-warrior-poet to edit his tradition’s holiest text and add nothing of himself – that is extraordinary humility.

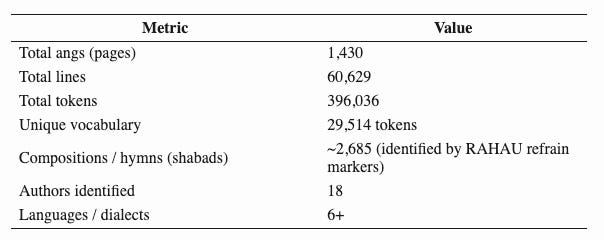

Length, Languages & Lexicon

Six Languages, One Script

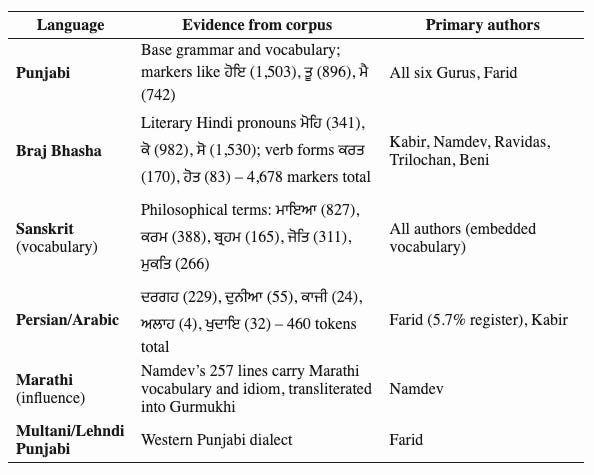

The entire GGS is written in Gurmukhi script, but the underlying text draws on at least six distinct languages and dialects:

Braj Bhasha grammatical markers (4,678) slightly outnumber Punjabi-specific markers (3,656) in raw count – reflecting the substantial Bhagat contribution. Scholars call this composite literary language “Sant Bhasha” (saint’s language) – a lingua franca blending Braj Bhasha, Awadhi, Punjabi, and regional vocabularies, unified by Gurmukhi script. For full corpus statistics and language analysis, see the corpus overview.

Compositional History

The GGS was compiled in two major stages:

Adi Granth (1604) – Guru Arjan compiled the first edition, incorporating compositions by Guru Nanak through Guru Arjan (Mahalla 1-5 – the numbering system identifying each Guru’s compositions), plus the 13 Bhagats. Guru Arjan is both the largest single contributor (42.9%) and the editor who shaped the text’s overall structure and character.

Damdami Bir (1706) – Guru Gobind Singh added Guru Tegh Bahadur’s compositions (Mahalla 9, 605 lines). Tradition holds that Guru Arjan had left space in the original compilation anticipating future compositions – Guru Tegh Bahadur’s bani (sacred compositions) was inserted into the existing raga framework rather than appended as a separate section.

This editorial design explains why Guru Tegh Bahadur’s compositions appear distributed across the same ragas as the earlier Gurus, maintaining the organizational integrity of the original compilation.

What I Measured

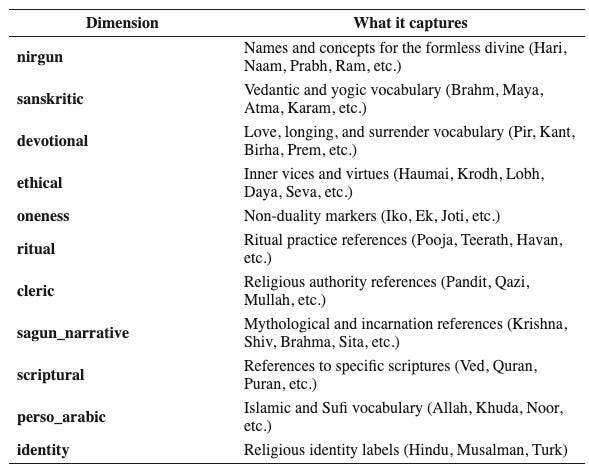

To analyze the text computationally, I built a lexicon of 124 theological entities with 346 spelling variants in Gurmukhi, organized across eleven dimensions:

This lexicon yielded 60,012 matches across the corpus – 57.3% of all lines contain at least one recognized entity. 114 of 124 entities matched at least once. Every percentage and finding in this blog traces back to these matches. For the full lexicon design and feature dimensions, see the feature documentation.

Musicality & Shabads

The GGS is not a book you read silently. It is a performed text.

Every composition is built around a RAHAU (ਰਹਾਉ) – a refrain, a pause, a line of emotional intensity that anchors the shabad. Our pipeline identifies ~2,685 compositions by these refrain markers. Each one is a complete unit: a poem with a heart-cry at its center.

These compositions are organized into 31 ragas – melodic modes from Indian classical music. Each raga prescribes how the composition should be sung, carrying its own emotional and seasonal character.

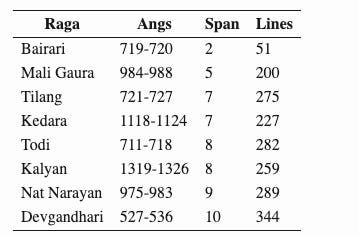

Largest ragas (the bulk of the GGS):

Smallest ragas (concentrated, specialized compositions):

Gauri alone (196 angs, 9,626 lines) contains more text than the 10 smallest ragas combined. The range from 2 angs (Bairari) to 196 angs (Gauri) reflects the varying depth of compositional engagement with each musical mode. The Gurus didn’t distribute evenly – they concentrated their engagement heavily in certain emotional registers. For the full raga breakdown and structure, see the corpus overview.

This isn’t a text organized by topic or chronology. It’s organized by emotion.

Entities Referenced

So what does the text actually talk about? Here’s the structural map.

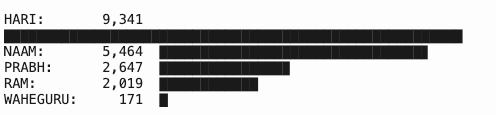

Divine Names

HARI appears 55 times for every 1 occurrence of WAHEGURU. More on this later. For the full entity frequency rankings, see the matching results.

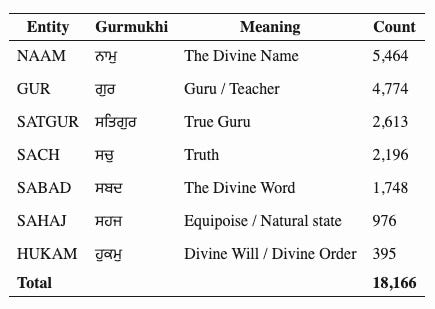

Core Sikh Vocabulary

These are the distinctive theological concepts of the tradition – and they account for 18,166 matches, 30% of all entity matches in the corpus:

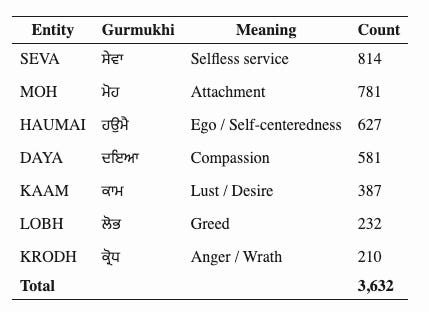

Ethical Vocabulary

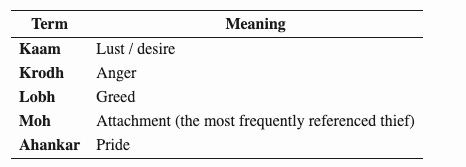

The Five Thieves (Panj Chor) plus virtues – the inner moral landscape the GGS maps obsessively:

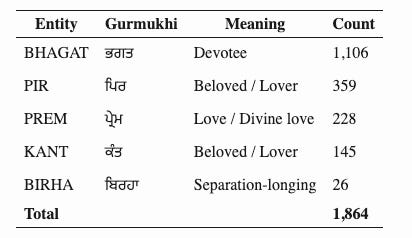

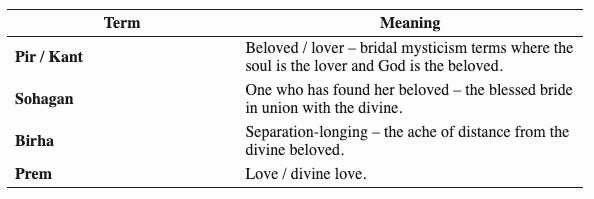

Devotional Vocabulary

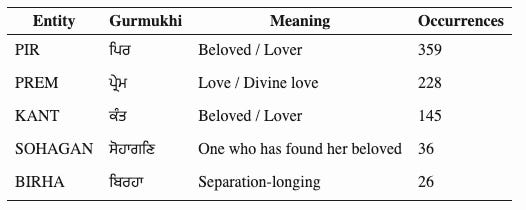

The bridal mysticism, the love-longing, the devotional surrender:

Epic and Mythological Figures

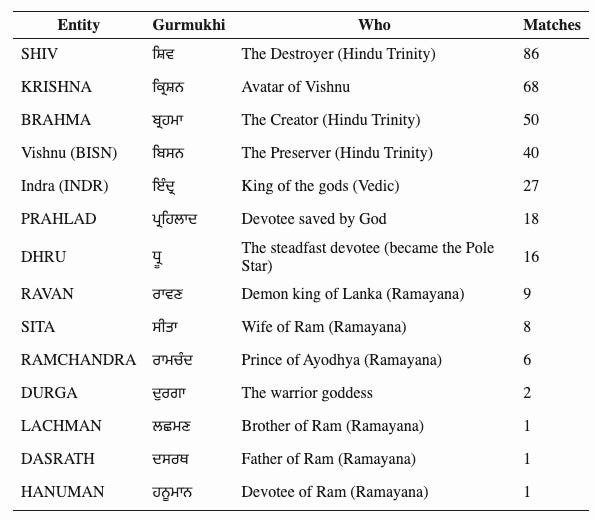

This is where it gets striking. The entire cast of Indian mythology is nearly absent:

The complete cast of the Ramayana (one of Hinduism’s two great epics) – Sita, Dasrath, Ravan, Lachman, Hanuman, Ramchandra – appears in only 26 lines combined. HARI alone appears in 9,341. The GGS uses these figures sparingly, almost always subordinated to nirgun teaching. For the complete entity frequency tables, see the matching results.

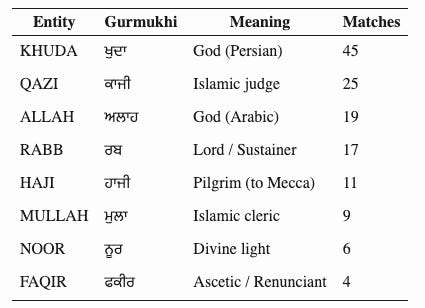

Perso-Arabic Terms

Only 136 matches across 8 entities:

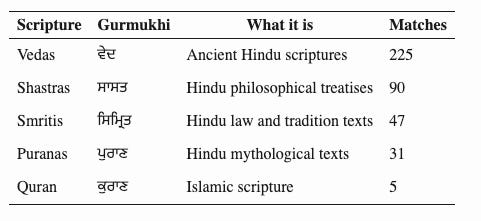

Scriptural References

One of the most unexpected findings: NA_NEGATION (ਨਾ, 2,229 matches) and BINU_NEGATION (ਬਿਨੁ, 1,656 matches) are in the top 12 entities in the entire corpus. These are negation markers – “without,” “not,” “beyond.”

The GGS defines the divine through negation. Without fear. Without enmity. Without form. Without birth. The data literally shows a text that describes God by saying what God is not. This is the apophatic tradition – theology by negation – and it runs through the entire text, not as a rare technique but as one of the most frequent structural patterns in the corpus. For semantic analysis of entity relationships, see the semantic analysis.

Each Guru’s Voice

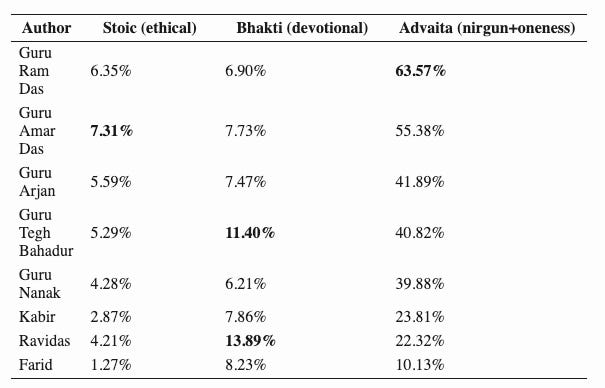

The GGS has 18 authors, but they are not interchangeable. The data reveals distinctive theological voices – each Guru gravitating toward different registers, different preoccupations, different ways of reaching the same formless divine.

One striking continuity device: all six contributing Gurus sign as “Nanak.” NANAK appears 5,000 times in the text. Guru Arjan, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das – they all use “Nanak” as their signature, not their own names. They saw themselves as one lineage, one light passing through different bodies.

Six Gurus account for 90.4% of the text. Twelve Bhagats and Sundar (a bard who recorded a deathbed dialogue) contribute the remaining 9.6%.

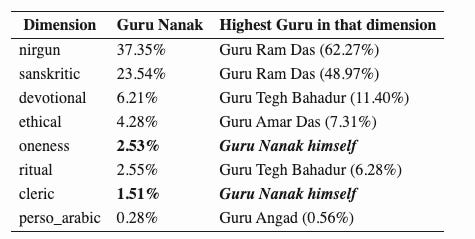

The Distinctive Voices

Guru Arjan: The Compiler-Poet. 42.9% of all lines – nearly as much as the next three Gurus combined. As both the compiler of the Adi Granth and its most prolific contributor, his register profile is broadly representative of the corpus mean. His editorial choices shaped the character of the text as a whole.

Guru Nanak: The Balanced Founder. He isn’t the highest in any single dimension except two – but he’s the only author who engages meaningfully with all of them:

He leads in oneness and cleric critique – the universalist and the reformer. Every subsequent Guru took one dimension of Nanak’s template and turned up the volume. Ram Das amplified nirgun. Amar Das amplified ethics. Tegh Bahadur amplified devotion. But Nanak laid the entire territory.

Guru Ram Das: The Nirgun Maximalist. 62.27% nirgun density – the highest of any author. His compositions are saturated with HARI (3,663 occurrences – once every 1.9 lines). Nearly two-thirds of his lines contain formless-divine vocabulary.

Guru Amar Das: The Ethical Voice. Highest ethical density (7.31%) among the Gurus. His compositions emphasize inner moral transformation – SABAD (801), SACH (880), SAHAJ (318) dominate his vocabulary.

Guru Tegh Bahadur: The Devotional-Detachment Philosopher. Highest devotional density (11.40%) and highest ritual engagement (6.28%) among the Gurus. He combines deep longing with sustained engagement with external practice. And he has zero Perso-Arabic vocabulary – the only Guru with no Islamic register at all.

Kabir: The Cross-Tradition Voice. A Muslim weaver whose 4,187 lines carry the highest identity marker density (0.55%) – he’s where Hindu-Muslim vocabulary most frequently appears together. His Perso-Arabic density (1.43%) is the highest among major contributors.

Farid: The Sufi Outlier. The only author whose Perso-Arabic density (5.70%) exceeds his nirgun density (10.13%). His 158 lines read as Sufi devotional poetry – BIRHA (separation-longing) appears 5 times in those 158 lines alone.

Ravidas: The Devotional Peak. Highest devotional density (13.89%) of any author in the entire corpus. A leather-worker considered untouchable by caste Hindus, his 475 lines are the most intensely devotional voice in the GGS.

For detailed register profiles, ASCII charts, and top entities for each author, see the full author analysis.

The Three Pillars

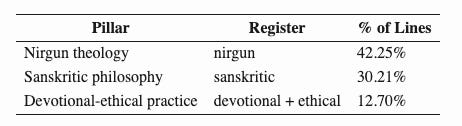

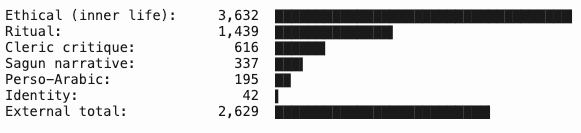

Step back from the individual entities and a structural pattern emerges. Three dominant modes of discourse account for 85.2% of all theological vocabulary in the GGS:

Everything else – ritual critique (2.20%), interfaith engagement (0.29%), mythological narrative (0.51%), identity labeling, Perso-Arabic vocabulary – all of it combined is less than one-sixth of the text.

The things people argue about most – is the GGS Hindu or not, what about Islam, what about ritual, what about caste – occupy a sliver of the text. The overwhelming majority is formless theology, philosophical vocabulary, devotion, and ethics. The data doesn’t leave much room for ambiguity about what the Gurus were focused on.

For the full dimension-by-dimension breakdown, see the feature analysis.

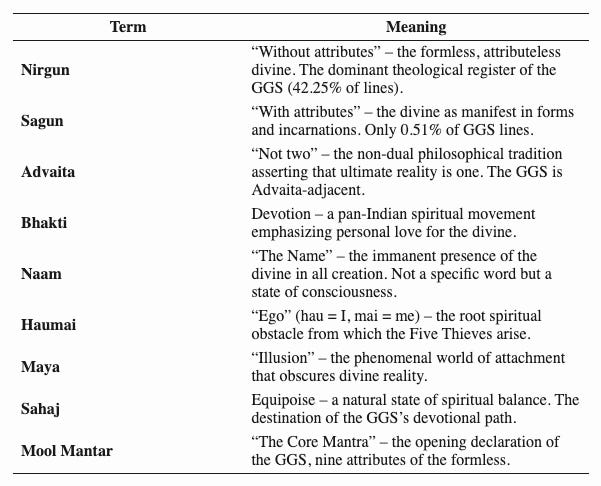

The Advaita Connection

This is the central finding, and it requires some precision.

Nirgun means “without attributes” (nir = without, gun = qualities). Advaita means “not two” (a = not, dvaita = duality). Both point to the same reality: a formless, non-dual divine that cannot be named, imaged, or incarnated. The GGS’s nirgun theology is Advaita-adjacent – they share the same metaphysical core.

The numbers: 42.25% nirgun + 2.0% oneness markers = 44.25% Advaita-adjacent content. Nearly half the text.

The Sanskritic vocabulary (30.21% of lines) reinforces this, not contradicts it. The Gurus used Maya (ਮਾਇਆ, 827 occurrences), Brahm (ਬ੍ਰਹਮ, 165), Karam (ਕਰਮ, 620), Atma, Mukti – the entire Vedantic toolkit. The GGS talks at length about the world as Maya, about the dissolution of ego, about the identity of the soul with the One. The Gurus didn’t reject Vedantic philosophy. They engaged with it deeply and recontextualized it within a nirgun framework.

Sagun narrative – references to incarnations, mythological figures – appears in only 0.51% of lines. When incarnation stories do appear, they almost always serve nirgun teaching (more on this in The Sanatan Question).

Nirgun Bhakti: Advaita Wrapped in a Love Poem

But here’s what makes the GGS different from Advaita Vedanta. Shankara, the 8th-century philosopher who systematized Advaita Vedanta, found non-duality through philosophical analysis – pure intellect, no emotion required. The GGS finds the same formless reality through song. Through love. Through the ache of separation and the ecstasy of union.

Scholars call this “nirgun bhakti” – devotion to the formless. It’s a unique philosophical position: Advaita’s metaphysics combined with Bhakti’s emotional surrender. The data confirms it: 44.25% Advaita-adjacent content sitting alongside 7.24% devotional vocabulary. The formless divine and the bridal love poem occupy the same text, often the same line.

Advaita, in its classical Vedantic form, is intellectual. It’s hard for people to grasp. The dissolution of the self into Brahman (the ultimate reality, not to be confused with Brahma the creator god), the unreality of the world, the logic of neti-neti (“not this, not this”) – this is philosophy for the scholar’s study. The GGS took that same non-dual insight and made it accessible by blending it with emotion. You don’t need to follow Shankara’s chain of reasoning. You need to feel it. The Gurus democratized Advaita – they took the most abstract metaphysics in the Indian tradition and set it to music.

As Osho, the Indian spiritual teacher, observed, Nanak’s place is unique – he found the formless not through renunciation or intellectual dissection, but by singing to it. Just the joy. Just the love. And this connects back to the ragas: every poem in the GGS is wrapped in music, set to a melodic mode that prescribes the emotion. The path to the formless isn’t through austerity or analysis. It’s through beauty.

In today’s language, one might think of this as a quantum field – a nameless, formless energy pervading all creation. The Gurus would have understood the metaphor. But they would have added: you don’t just observe the field. You immerse in the formless light and sing to and with it.

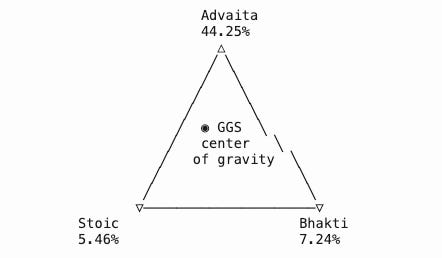

The Stoic-Bhakti-Advaita Triangle

Every author in the GGS engages with three axes – but in different proportions:

The GGS’s center of gravity sits high and slightly right – overwhelmingly Advaita, with Bhakti outweighing Stoic ethics. Each author occupies a different position within this space:

Guru Ram Das sits nearest the Advaita apex (63.57%). Ravidas pulls hardest toward the Bhakti corner (13.89%). Guru Amar Das leans most toward Stoic ethics (7.31%). Farid, the Sufi, sits lowest on the Advaita axis (10.13%) and highest on Bhakti among the Bhagats. But no author is purely any one thing. Every voice in the GGS carries all three currents.

The GGS is not pure Advaita. It is not pure Bhakti. It is not pure Stoic ethics. It is nirgun bhakti – Advaita wrapped in a love poem, sung in ragas, concerned with the mastery of the inner life. That combination is quantitatively unique.

For the full semantic analysis and Stoic-Bhakti-Advaita breakdown by author, see the semantic analysis.

HARI, Not WAHEGURU

This genuinely surprised me. If you grow up in the Sikh tradition today, the two names you hear most are Naam and Waheguru. The data tells a different story.

HARI (ਹਰਿ) appears 9,341 times – more than any other entity in the text. WAHEGURU (ਵਾਹਿਗੁਰੂ) appears 171 times. That’s a 55:1 ratio.

Modern Sikh practice centers on “Waheguru” as the primary name for God. The text itself centers on Hari, Naam, and Prabh. This isn’t a contradiction – it’s an evolution. WAHEGURU became the primary name in the later tradition, post-GGS. But the scripture itself speaks a different lexical language than modern practice.

For the full entity frequency rankings, see the matching results.

The Sanatan Question

The questions that started this project were simple: how much of the text has Sanatan roots, and what percentage references Indian gods? The answers came back in layers, each more nuanced than the last.

Layer 1: The Gods Are Pointers, Not the Point

The Gurus didn’t erase the gods. They embraced the names – Shiv (86 occurrences), Krishna (68), Brahma (50), Vishnu (40) – but understood each as a finger pointing at the formless light, not as the light itself. The complete Ramayana cast – Sita (8), Dasrath (1), Ravan (9), Lachman (1), Hanuman (1), Ramchandra (6) – appears in only 26 lines combined out of 60,629. The gods are present, but proportionally, the Gurus spent 83x more lines on the formless itself than on the pointers to it.

And here’s what the data confirms: when these figures do appear, 27% of those lines also contain nirgun vocabulary. A characteristic line invokes Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva to argue that even they do not know the divine – using the gods to assert the formless. This is no different from Krishna saying in the Gita that he is the avatar of the formless Vishnu, or Advaita’s core insight that every name, every form, every person is Brahman. The Gurus were doing the same thing – pointing through the names to what lies beyond them.

What does “Ram” actually mean? The clearest proof that the gods are pointers is RAM (ਰਾਮ) itself. It appears 2,019 times across 1,894 lines – one of the most frequent entities in the corpus. If you’re counting “references to Indian gods,” that’s a big number. But the analysis has to go deeper than lexical matching. What does the word mean in the semantic context the Gurus placed it in?

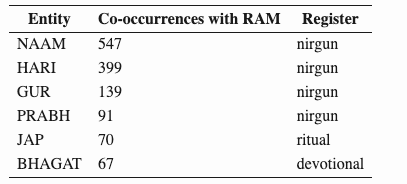

The co-occurrence data is unambiguous:

Every top companion is nirgun-register. RAM co-occurs with sagun narrative entities (Krishna, Shiv, Brahma, Sita) only 7 times at ang level, compared to 27 nirgun co-occurrences. RAM’s semantic neighborhood is indistinguishable from HARI’s.

RAM in the GGS behaves statistically as a synonym for the formless divine, not as a reference to Dasharatha’s son. The most frequently used “god name” in the text is itself a nirgun word. The pointer and the formless are the same.

Layer 2: The Vocabulary Ratio

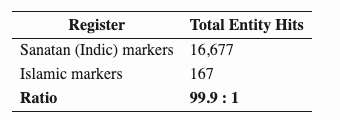

Now zoom out from individual words to the entire vocabulary. The civilizational density ratio:

For every 1 Islamic-register entity (Allah, Khuda, Qazi, Noor, etc.), there are 99.9 Sanatan-register entities (Hari, Naam, Brahm, Maya, Ram, etc.). The Perso-Arabic register appears in only 0.29% of lines (174 lines out of 60,629). The Sanskritic register appears in 30.21% and the nirgun register in 42.25%.

The GGS’s vocabulary is overwhelmingly Sanatan-derived. But – and this is crucial – it is Sanatan vocabulary repurposed for nirgun theology. The word “Ram” doesn’t mean the prince. “Hari” doesn’t mean Vishnu. “Brahm” doesn’t mean the creator god. The Gurus took the entire Sanskritic lexicon and pointed it at the formless.

Layer 3: When ALLAH Appears

ALLAH appears in only 19 lines of the entire corpus (0.03%). When it does appear:

21% of those lines also contain Indic divine names (RAM, HARI)

ALLAH co-occurs with KHUDA (3 times) and NOOR (2 times)

The context is consistently universalist-mystical, not legalistic

These are the “Aval Allah Noor Upaya” (“First, Allah created the Light”) lines – moments of explicit civilizational synthesis where the text deliberately bridges Islamic and Indic vocabulary.

Layer 4: HINDU and TURK – Always Together

The most statistically surprising finding in the entire corpus: HINDU and TURK have the highest PMI (6.174) of any entity pair – higher than any divine name cluster, any mythological grouping, any ritual pairing.

When the GGS names religious communities, it names them together. Always. The text structurally refuses to critique one community without addressing both. Only 31 lines in the entire 60,629-line corpus contain explicit religious identity labels. The GGS almost never names communities. When it does, it names them as a pair to transcend.

A linguistic note: the GGS’s primary term for Muslims is TURK (ਤੁਰਕ), not Musalman (which appears in only ~7 lines). “Turk” is an ethnic-political term – it references the Central Asian Turkic rulers of medieval India – the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) and early Mughal Empire, the Muslim dynasties that governed the subcontinent during the Gurus’ era. The Gurus used a word that identifies this community by its foreign political origin rather than by its religious identity. Whether this reflects that the Muslim community was still primarily associated with the ruling class and not yet fully integrated into the indigenous fabric, or simply the common colloquial term of 15th-17th century Punjab, is a question I’ll leave to historians. But the word choice is striking.

Layer 5: How the Text Achieves Its Multi-Traditional Character

Register mixing at the line level is almost nonexistent – only 0.12% of register-carrying lines contain both Perso-Arabic and Sanskritic vocabulary on the same line. The GGS achieves its multi-traditional character through composition-level juxtaposition, not line-level blending. Kabir’s compositions sit next to Guru Arjan’s. Farid’s Sufi verses share the same raga section as nirgun hymns. This is deliberate editorial design – the diversity is structural, woven into the organization of the text itself.

The Answer

So how Sanatan is the GGS? The vocabulary is 99.9% Sanatan-derived. But the theology transcends Sanatan tradition just as it transcends Islamic tradition. The Gurus took the Sanskritic lexicon – Ram, Hari, Brahm, Maya, Atma – and redirected every word toward the formless. They didn’t reject the vocabulary. They repurposed it. And in the rare moments when they engaged Islamic vocabulary, they did so to synthesize, not to divide.

This does not mean the GGS is “Hindu.” The nirgun theology explicitly transcends both Hindu and Islamic categories. But the vocabulary through which that transcendence is expressed is overwhelmingly drawn from the Sanskritic-Punjabi lexical register.

For the full RAM analysis, ALLAH context, and civilizational density ratios, see the semantic analysis. For register mixing patterns, see the mixing analysis.

The Five Thieves and Inner Sovereignty

The GGS devotes 5.46% of all lines to ethical vocabulary – inner vices and virtues, the moral psychology of the self. It devotes 2.20% to ritual references – pilgrimage, fire ritual, idol worship. That’s a 2.5:1 ratio. The text cares 2.5 times more about what’s happening inside you than about what you’re doing at the temple.

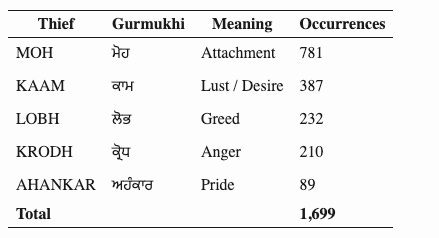

The Five Thieves (Panj Chor)

Sikh theology names five inner enemies – the Panj Chor (Five Thieves) – that steal the mind’s capacity for the divine. The GGS maps them obsessively:

The ordering is the data’s, not mine. Moh (attachment) dominates – it appears nearly as often as the next two thieves combined. The GGS’s primary ethical concern isn’t lust or anger, as in many ascetic traditions. It’s attachment to the world. Worldly entanglement. The inability to let go. This is distinctly non-ascetic – the text isn’t against the body or against desire per se. It’s against the grip that the world has on the mind.

Then there’s HAUMAI (ਹਉਮੈ) – ego, self-centeredness – which the GGS tracks separately at 627 occurrences. In Sikh theology, Haumai is the root from which the Five Thieves arise. Ego creates attachment. Attachment breeds desire. Desire produces anger when thwarted, greed when indulged, pride when satisfied. If you include Haumai alongside the traditional five, the total rises to 2,237 matches.

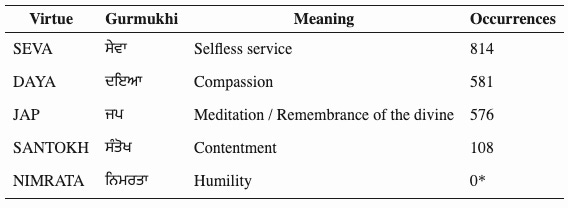

The Virtues

The GGS doesn’t just diagnose. It prescribes

*NIMRATA returned zero matches – a known lexicon limitation. The word exists in the GGS but our spelling variants didn’t capture its actual orthography. This is one of 10 unmatched entities in the 124-entity lexicon.

Seva alone (814) outranks every individual thief except Moh. Jap – the practice of meditating on the divine Name – appears 576 times, making it the third most frequent virtue. The text gives as much weight to the cultivation of service, compassion, and remembrance as it does to the diagnosis of vice. This is a complete ethical system – not just “avoid evil” but “actively cultivate good.”

The Quantitative Knockout

Here’s what struck me most: the 3,632 ethical entity matches exceed ritual (1,439), cleric critique (616), sagun narrative (337), Perso-Arabic (195), and identity (42) – combined (2,629). The inner life gets more textual attention than every external category put together.

The Stoic Parallel – With a Twist

This maps remarkably well to Stoic philosophy. Inner sovereignty. Mastery of the passions. Cultivation of virtue. Equanimity in the face of the world’s chaos. Marcus Aurelius would recognize the language – conquer the thieves within, and the world outside loses its power over you.

But the GGS goes somewhere Stoicism doesn’t. For the Stoics, self-mastery is the destination. For the Gurus, it’s the prerequisite. You conquer the Five Thieves not to achieve ataraxia (Stoic calm) but to dissolve the ego that separates you from the formless. Ethics clears the path. Nirgun theology is what lies at the end of it.

The Five Thieves are not the enemy. Haumai – the ego that gives them power – is the enemy. And the cure for Haumai is Naam – the dissolution of self into the formless divine. The ethical and the theological are not separate dimensions in the GGS. They are two stages of the same journey.

For the full ethical dimension analysis, see the feature analysis. For entity frequencies, see the matching results.

A Love Poem to the Infinite

The GGS is not just philosophy. It’s a love poem. And like any love poem, it has a structure: a lover, a beloved, a longing, and a resolution.

The Bridal Metaphor

The GGS’s central devotional device is bridal mysticism – the soul as the lover, God as the beloved. This isn’t occasional imagery. It’s a sustained literary architecture with its own vocabulary:

The soul speaks as a lover waiting for the beloved to come home. The Sohagan – the blessed one, the one who has found her beloved – is the GGS’s image of spiritual fulfillment. Not enlightenment as intellectual achievement. Not salvation as rescue from punishment. Union. The lover finds the beloved.

The Emotional Engine Is Separation, Not Union

BIRHA (26 occurrences) is small in count but enormous in function. The dominant emotional state in the GGS is longing, not arrival. The lover aches for the beloved who is felt but not seen. The night is dark. The bed is empty. The beloved is everywhere and yet the lover cannot hold on.

This is the emotional engine of the entire devotional register. The GGS doesn’t describe the joy of union nearly as much as it describes the ache of separation. And that ache is what drives the devotee deeper – into Naam, into Sahaj, into the dissolution of the self that separates lover from beloved.

RAHAU: The Heart-Cry

Every shabad is built around a RAHAU (ਰਹਾਉ) line – 2,685 of them across the text. RAHAU means “pause.” It’s the refrain, the line you return to, the emotional core of the composition. A shabad isn’t a linear argument. It’s a poem that circles around its own center of gravity – a cry repeated, a truth returned to after each verse.

The RAHAU line is where the poet’s voice breaks through most directly. It’s the line that gets sung again and again. In a text of 60,629 lines, there are 2,685 of these emotional anchors – one for roughly every 22 lines. The entire text is punctuated by pauses, by heart-cries, by returns to what matters most.

SAHAJ: Where the Love Poem Resolves

SAHAJ (ਸਹਜ) appears 976 times – one of the most frequent entities in the entire corpus. The destination of devotion isn’t ecstasy or trance. It’s Sahaj – equipoise, a natural state of spiritual balance. Stillness. Calm.

The love poem resolves not into frenzy but into peace. The lover doesn’t burn forever. The ache of Birha, the longing of Prem, the crying out for the Pir – it all resolves into Sahaj. The beloved was never absent. The separation was Haumai – the ego that imagined it was separate. When the ego dissolves, Sahaj remains.

Philosophy and Longing in the Same Line

Here is the paradox that makes the GGS unique: the text moves between metaphysical abstraction and raw emotional ache within the same compositions, often within the same line. A line will assert the unreality of the world (Maya) and then cry out for the beloved (Pir) in the next breath. The Gurus saw no contradiction. The philosophy says the divine is formless. The poetry says: and I love it as my beloved anyway.

This is nirgun bhakti at the line level. Not “formless theology” in one section and “love poems” in another. Both, simultaneously, woven into the same verse. 7.24% of all lines carry devotional vocabulary, and much of it appears alongside nirgun entities. The Stoic and the lover sit in the same line.

For devotional entity frequencies, see the matching results. For the devotional dimension analysis, see the feature analysis.

What Kind of Text Is This?

Is the GGS a Bhakti text? An Advaita text? A Stoic-ethical text? An interfaith text? A Sanatan text?

The data says: it is all of these and none of them. It is a convergence text that:

Speaks overwhelmingly in nirgun vocabulary (42.25%) – nearly half the text is about a formless divine that cannot be named, imaged, or incarnated.

Engages deeply with Sanskritic philosophy (30.21%) – Maya, Brahm, Atma, Karam. The Gurus didn’t reject Vedantic thought. They repurposed its entire lexicon for nirgun theology.

Sustains a powerful devotional register (7.24%) – love poems to the formless. Bridal mysticism, separation-longing, the ache of Birha resolving into the stillness of Sahaj.

Prioritizes inner sovereignty over external ritual (5.46% vs 2.20%) – the Five Thieves and their cure get 2.5x more attention than pilgrimage, fire ritual, and idol worship combined.

Uses mythology as pointers to the formless, never as standalone narrative – the gods appear (Shiv, Krishna, Brahma, Vishnu) but 83x less often than the formless itself, and 27% of those lines also contain nirgun vocabulary.

Engages Islamic vocabulary rarely but with deliberate synthesis (0.29%) – when ALLAH appears, 21% of those lines also contain Indic divine names. The 99.9:1 vocabulary ratio is Sanatan, but the theology transcends both traditions.

Treats religious identity as something to transcend, not to defend – HINDU and TURK have the highest PMI in the entire corpus. When the text names communities, it names them together. Always.

This combination is quantitatively unique. That isn’t a claim of superiority. It’s a structural observation from the data. No other scripture has this particular architecture: Advaita metaphysics expressed through devotional longing, grounded in ethical self-discipline, spoken in Sanskritic-Punjabi vocabulary, with selective cross-civilizational synthesis – all set to music.

The Dark Matter

But this analysis captures only half the text. 49.7% of lines are unmarked by our 124-entity lexicon. We’ve mapped the theological skeleton – the divine names, the philosophical vocabulary, the ethical terms, the devotional metaphors, the identity markers. But the poetry, the grammar, the Gurmukhi wordplay, the emotional texture of individual lines – that’s the flesh we haven’t measured.

The unmarked lines aren’t empty. They’re full of connective tissue – the narrative, the imagery, the turns of phrase that make the GGS poetry and not just a catalogue of theological terms. Our lexicon captures what the text talks about. It doesn’t capture how it talks. That’s the next frontier.

Limitations

This analysis is honest about what it can and cannot do:

String matching, not semantic disambiguation. The pipeline matches Gurmukhi tokens. It doesn’t understand context. When ਕਰਮ appears, it could mean karma, action, or grace – we count it once under KARAM.

Polysemous terms (ਕਰਮ, ਕਾਮ, ਜਗ, ਪਿਰ, ਮੂਰਤਿ) are flagged but not disambiguated. Five entities in our lexicon carry multiple meanings.

Co-occurrence is measured at ang level, not shabad level. The corpus lacks shabad boundary markers. Ang-level grouping is coarser than ideal.

Author attribution is regex-based – Mahalla headers and Bhagat signatures. Lines near section boundaries may be misattributed.

10 of 124 entities returned zero matches, including NIMRATA (humility) – a core Sikh virtue whose GGS orthography our spelling variants didn’t capture.

The Invitation

This project is open source and fully reproducible. The pipeline processes raw Gurmukhi – no English translation drives any analytical logic. Every percentage, every count, every finding traces back to specific lines and entity matches.

I’m not a data scientist. I wrote the product requirements with ChatGPT and the code with Claude. If there are issues, the project is on GitHub. File a bug. Fork the repo. Improve the lexicon. Add the missing spelling variants. Build a shabad-level co-occurrence engine. Measure what we haven’t measured.

The numbers don’t interpret theology. They describe what the text actually does, line by line, word by word. And what it does is remarkable.

For the full analysis – all 13 findings, methodology, and per-author breakdowns – see the complete analysis documentation.

Coming Home

What I didn’t expect was what the data would show me about myself.

I spent three decades walking the earth, exploring philosophies. I studied meditation traditions, read the Stoics, sat with teachers from different lineages. Eventually I landed on Advaita – non-duality. The formless. And I found my practice settling into something Sahaj-based – not devotional intensity, not intellectual analysis, but equipoise. Joy. The natural state.

Then the data came back. 44.25% Advaita-adjacent. SAHAJ appearing 976 times – one of the most frequent entities in the entire text. Nirgun bhakti: Advaita wrapped in a love poem. The Mool Mantar was always Advaita in one breath. Every word – formless, timeless, beyond species, without fear, without enmity – was pointing where I eventually arrived by walking the long way around.

I truly walked the earth and came home to find the lessons were here already.

The data didn’t tell me what to believe. It showed me what was always there. The 99.9% Sanatan vocabulary, but a theology that transcends both Hindu and Islamic categories. The gods as pointers, not the point. The Five Thieves as the real obstacle, not the wrong temple. HARI, not WAHEGURU. Ram as the formless, not the prince. And through it all, the love poem – the ache of Birha resolving into the stillness of Sahaj.

The Gurus knew. They always knew.

Quick Glossary

For readers unfamiliar with the terminology. A full glossary is available in the project documentation.